The Bike Lane Effect on Harvard Bridge

MIT • Decarbonizing Urban Mobility

Spring 2024

There is limited existing research examining the impact of past cycling infrastructure improvements in Boston on ridership, mode shift, or emissions reductions. This is largely due to the fact that the most installations of separated bike infrastructure in Boston have occurred within the last decade. One of the earliest of these projects, the Commonwealth Avenue full-build separated bike lane that traverses through Boston University’s central campus, was completed in 2019 [1]. A 2021 study analyzed the impact of this project on local ridership of Boston’s bicycle-sharing (“bikeshare”) system, BlueBikes. Using a model that controlled for seasonal and citywide effects on bike ridership, the study found that the new bike lane increased bikeshare ridership by 80 percent on affected station-to-station routes [2]. Since this study has been released, however, the city has implemented multiple similar projects, promting a renewed look.

MassDOT completed a road diet project on the Harvard Bridge between 2021 and 2023, removing one traffic lane in each direction to create a quick-build protected bike lane. The project began with a pilot in November 2021, when cones were temporarily installed to define the new lanes. These lanes were then painted in mid-2022 and permanent flex posts were installed in October 2023. We analyzed bicycle trip data before and after the November 2021 pilot start date, as the temporary lanes were functionally identical to the permanent painted lanes and caused a spike in cycling ridership.

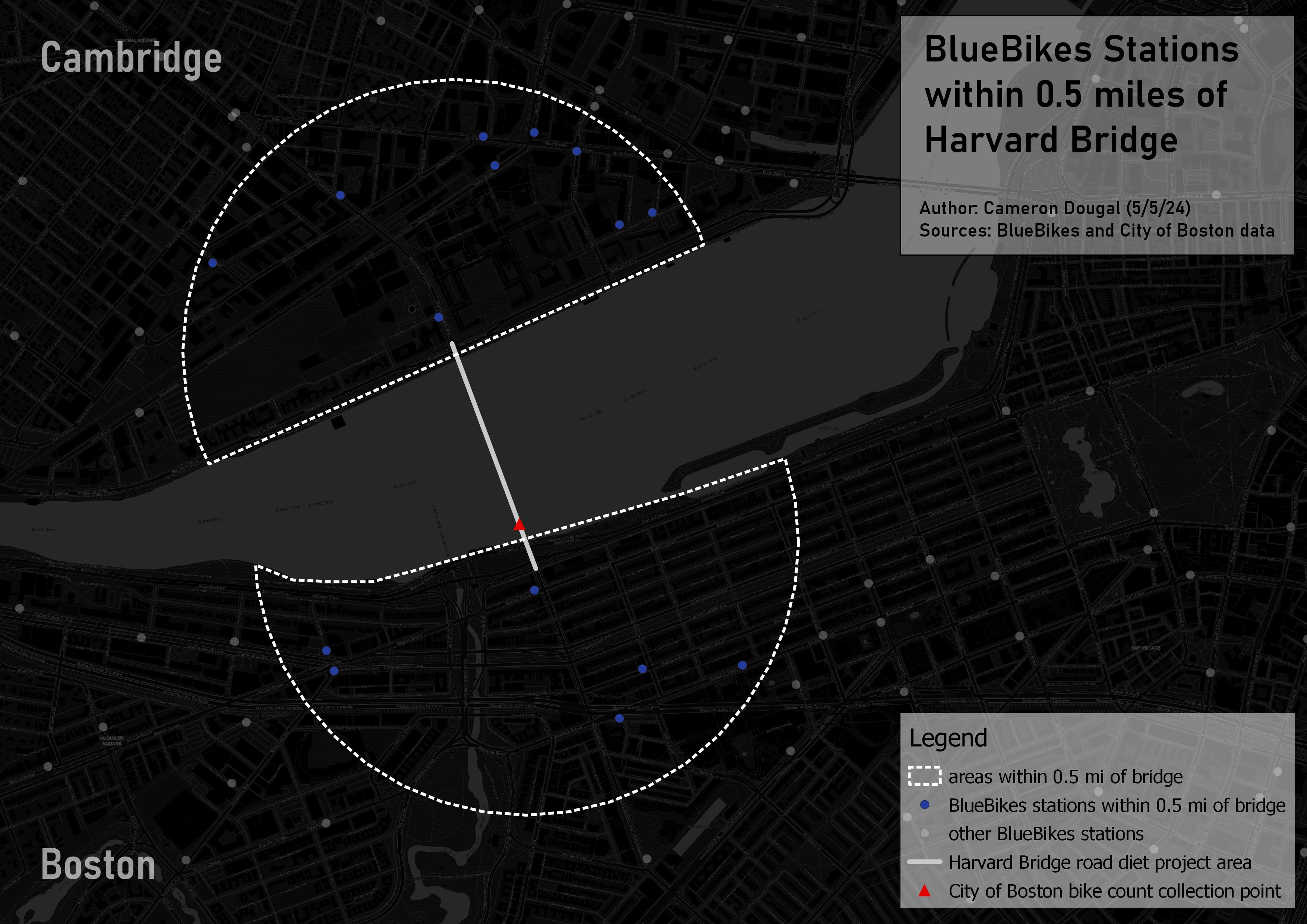

Because of the trip-funneling nature of the bridge and the lack of alternate routes for many trips, this redesign offered a unique opportunity to isolate the project’s impact on cycling trips. The most comprehensive cycling trip data available is BlueBikes trip data, which includes the datetime and start/end stations for every trip taken on the system [3]. By isolating the trips that began and ended on opposite sides of the Charles River, we can analyze the change in the number of trips that were extremely likely to have used the bridge.

Figure 3 demonstrates that between December 2021 (immediately after the beginning of the redesign pilot) and Summer 2022 (before September, when the BlueBikes trips plateau at an upper limit of possible daily trips), BlueBike ridership on the bridge increased significantly. This increase in trips can also be observed in the 2023 data. For each month within a six-month period during redesign pilot, we can plot the increase in trips versus the number of trips in the same month of the previous year:

Despite a system-wide increase of trips of 136% during the six-month period after the beginning of the redesign pilot (versus the same six months of the previous year), trips across the bridge increased by 182% (a nearly identical result to the Commonwealth Avenue study referenced in the introduction to this section). Translating to actual trip counts, trips across the bridge during this six-month period were 5,787 higher than what can be explained by system-wide trip growth. These results can be further verified by analyzing City of Boston bike count data, which is collected four times per year using automated bike and vehicle counters for forty-eight hours [4].

Due to the restrictive manner in which the City of Boston bike count data is made available to the public, it was difficult to collect counts across all collection locations to determine to what degree the increase in Harvard Bridge bicycle trips outpaced the average increase of cycling trips across all of Boston. Future data scraping could allow this determination to be made in order to quantify the impact of the new bike lanes on ridership using purely bike count data. However, it was possible to compare the Harvard Bridge bike counts to the estimated BlueBikes trips across the bridge to estimate the average percent of all Harvard Bridge bike trips that were BlueBikes trips, at 2.88%. Combining this value with the calculated “excess” BlueBike trips (5,787 trips over 6 months) allows us to estimate that there were on the order of 400,000 cycling trips on the Harvard Bridge in 2022 that can be attributed to the improvement in cycling infrastructure, or approximately 1,095 per day. This reflects an average cycling ridership increase of about one-third on the bridge.

However, how do these new cycling trips contribute to decarbonization? There is a lack of research that ties increased cycling ridership directly to decreased vehicle miles traveled, as it can be difficult to determine what proportions of these ‘induced’ trips are the result of a change in travel mode versus “the making of a trip previously not considered an option (latent demand) or the increase in cycling trip frequency” [5] Some research considers the decrease in commuting by driving per mile of cycling infrastructure added, but decreases in driving only become perceptible when considering bike infrastructure expansion at the urban network scale [6]. Surveying cyclists may provide the most meaningful data: surveying of users of the ECOBICI bikesharing system in Mexico City found that 13.7-17.2% of users would have used a motor vehicle if they had not had access to the system [7]. This gives us a baseline to make the assumption that around one-tenth of the annual induced trips on the Harvard Bridge replaced a motor vehicle trip; however, translating this into carbon savings once again results in a negligible decrease in annual Boston urban transport emissions - meaningful emissions reductions are only realized as a cycling network is built out across the city. However, it is worth noting that small emissions reductions do not come at a high financial cost; though data on the final cost of the Harvard Bridge road diet project is not available online, quick-build projects generally cost only about $50,000 per mile [8], making them a cost-effective way to quickly scale a cycling network.

There are many limitations of this procedure. It assumes that the protected bike lane will increase cycling usage at the same rate as bikeshare usage; utilizes the percent of Harvard Bridge bike trips that were BlueBikes trips (2.88%) that has a large standard deviation of 1.84%; relies on an increase of BlueBikes ridership over a relatively short time span of six months; and does not account for the possibility that all BlueBikes stations close to the metro core (or close to MIT), not just those near the Harvard Bridge, saw a larger increase in ridership in early 2022 than the system average.

Bike count data must be significantly improved in order to track the effectiveness of these improvements and make the case for additional infrastructure investments in the future. The Harvard Bridge project was the only project we could find where bike count data lined up with a completed project. An analysis such as this would be most meaningful in an environmental justice community where cycling access can be more critical for residents, but current bike count data is collected too infrequently and in too few locations. The City of Boston should also collect more survey data from residents and bikeshare users to determine which types of cycling infrastructure are most effective for diverting car trips. Future studies could also refine methodologies for extrapolating from bikeshare trip data to total cycling trip data.

Appendix: Data Tables & References

Table A: Stations Used for Analysis of Harvard Bridge BlueBikes Trips

| Boston Station Names | Cambridge Station Names |

|---|---|

| Kenmore Square | Ames St at Main St |

| Boylston St at Massachusetts Ave | Galileo Galilei Way at Main Street |

| Deerfield St at Commonwealth Ave | Main Street/Albany Street/Technology Square |

| Boylston St at Fairfield St | Mass Ave at Albany St |

| Beacon St at Massachusetts Ave | MIT at Mass Ave / Amherst St |

| Newbury St at Hereford St | MIT Carleton St at Amherst St |

| MIT Hayward St at Amherst St | |

| MIT Pacific St at Purrington St | |

| MIT Stata Center at Vassar St / Main St | |

Table B: Estimated BlueBikes Trips Across Harvard Bridge

(Trips Using Stations in Table A, Beginning/Ending on Opposite Sides of Charles River)

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | * | 187 | 922 | 1332 |

| Feb | * | 237 | 1435 | 1690 |

| Mar | * | 560 | 1728 | 1990 |

| Apr | * | 1420 | 3223 | 3317 |

| May | * | 2678 | 4417 | 5666 |

| Jun | 499 | 1843 | 3323 | 4026 |

| Jul | 798 | 1922 | 4052 | 4401 |

| Aug | 959 | 3956 | 4734 | 4960 |

| Sept | 1123 | 9714 | 8979 | 5753 |

| Oct | 1325 | 8946 | 7015 | 5761 |

| Nov | 780 | 5106 | 4485 | 3567 |

| Dec | 203 | 1561 | 1599 | 1634 |

Table C: City of Boston Harvard Bridge Bike Counts and Estimated BlueBikes Trips

(BlueBikes Trips Using Stations in Table A, Beginning/Ending on Opposite Sides of Charles River)

For each collection day:

month |

collection date #1 |

bike count |

estimated BlueBikes trip count |

collection date #2 |

bike count |

estimated BlueBikes trip count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun-20 | 6/9/2020 | 1910 | 16 | 6/10/2020 | 2125 | 12 |

| Oct-20 | 9/22/2020 | 2882 | 32 | 9/23/2020 | 2945 | 36 |

| Dec-20 | 12/8/2020 | 993 | 8 | 12/9/2020 | 1026 | 4 |

| Mar-21 | 3/17/2021 | 1430 | 18 | 3/18/2021 | 671 | 11 |

| Jun-21 | 6/9/2021 | 2617 | 62 | 6/10/2021 | 3229 | 58 |

| Sep-21 | 9/29/2021 | 4232 | 302 | 9/30/2021 | 3933 | 310 |

| Dec-21 | 12/1/2021 | 2018 | 107 | 12/2/2021 | 2445 | 92 |

| Mar-22 | 3/22/2022 | 2072 | 33 | 3/23/2022 | 2017 | 40 |

| Jun-22 | 6/14/2022 | 4095 | 127 | 6/15/2022 | 3943 | 120 |

| Sep-22 | 9/28/2022 | 5759 | 249 | 9/29/2022 | 5744 | 237 |

| Dec-22 | 12/13/2022 | 2322 | 88 | 12/14/2022 | 1729 | 69 |

| Mar-23 | 3/15/2023 | 1898 | 61 | 3/16/2023 | 2883 | 78 |

| Jun-23 | 6/6/2023 | 4352 | 142 | 6/7/2023 | 4322 | 143 |

| Sep-23 | 9/20/2023 | 6331 | 199 | 9/21/2023 | 5988 | 204 |

Across both collection days:

month |

two-day bike count |

average daily bike count |

average daily bike count as % of combined bike and motor vehicle count |

two-day estimated BlueBikes trip count |

two-day estimated BlueBikes trip count as % of two-day bike count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun-20 | 4035 | 2018 | 14.06% | 28 | 0.69% |

| Oct-20 | 5827 | 2914 | 14.60% | 68 | 1.17% |

| Dec-20 | 2019 | 1010 | 5.90% | 12 | 0.59% |

| Mar-21 | 2101 | 1051 | 5.50% | 29 | 1.38% |

| Jun-21 | 5846 | 2923 | 12.00% | 120 | 2.05% |

| Sep-21 | 8165 | 4083 | 15.60% | 612 | 7.50% |

| Dec-21 | 4463 | 2232 | 9.60% | 199 | 4.46% |

| Mar-22 | 4089 | 2045 | 8.97% | 73 | 1.79% |

| Jun-22 | 8038 | 4019 | 14.93% | 247 | 3.07% |

| Sep-22 | 11503 | 5752 | 20.49% | 486 | 4.22% |

| Dec-22 | 4051 | 2026 | 8.54% | 157 | 3.88% |

| Mar-23 | 4781 | 2391 | 9.81% | 139 | 2.91% |

| Jun-23 | 8674 | 4337 | 16.61% | 285 | 3.29% |

| Sep-23 | 12319 | 6160 | 21.38% | 403 | 3.27% |

| AVERAGE | 2.88% | ||||

| STANDARD DEVIATION | 1.84% |